Adjoint of a Compact Operator

While studying for the 18.102 (Introduction to Functional Analysis) final this semester, I came across the following theorem, which I think is quite cool (see below for the relevant definitions).

In this post, I’ll explain a proof, based on the first answer to this Math StackExchange post.

Definitions and setup

First, here are some preliminary definitions (stated here for reference). Throughout this post, we work over $\mathbb{C}$.

- We say $X$ is a normed linear space if $X$ is a vector space together with a norm $\lVert \bullet \rVert$ satisfying the following three properties:

- $\lVert x \rVert \geq 0$ for all $x \in X$, with equality if and only if $x = 0$.

- Homogeneity — $\lVert \alpha x\rVert = \lvert \alpha \rvert \lVert x\rVert$ for all $x \in X$ and $\alpha \in \mathbb{C}$.

- The triangle inequality — $\lVert x + y \rVert \leq \lVert x \rVert + \lVert y \rVert$ for all $x, y \in X$.

A Banach space is a complete normed linear space.If $X$ is a normed linear space, then the norm induces a metric $d(x, y) = \lVert x - y\rVert$. When we say that $X$ is complete, we're referring to this norm. - Next, we'll state a few definitions regarding linear operators between normed linear spaces.If $X$ and $Y$ are normed linear spaces and $T \colon X \to Y$ is a linear operator, we say $T$ is bounded if there exists a constant $c$ such that $\lVert Tx\rVert \leq c\lVert x\rVert$ for all $x \in X$.If $T$ is a bounded linear operator, we define its operator norm as \[\lVert T\rVert = \sup_{x \neq 0} \frac{\lVert Tx\rVert}{\lVert x\rVert}.\]By homogeneity, we could equivalently define $\lVert T\rVert$ as $\sup_{\lVert x\rVert = 1} \lVert Tx\rVert$.If $X$ and $Y$ are normed linear spaces, then the set of bounded linear operators $T \colon X \to Y$ form a normed linear space as well (under the operator norm), which we denote by $\mathcal{B}(X, Y)$. Furthermore, if $Y$ is Banach, then so is $\mathcal{B}(X, Y)$.

- For a normed linear space $X$, its dual space $X^\ast$ is defined as $\mathcal{B}(X, \mathbb{C})$. We refer to elements of $X^\ast$ (which are bounded linear functions $f \colon X \to \mathbb{C}$) as functionals.Note that since $\mathbb{C}$ is Banach (i.e., complete), so is $X^*$ (for any normed linear space $X$).For any bounded linear operator $T \colon X \to Y$, we define its adjoint operator $T^* \colon Y^* \to X^*$ as the map such that $(T^\ast g)(x) = g(Tx)$ for all $g \in Y^\ast$ and $x \in X$.In other words, we're defining $T^\ast$ as the map sending each bounded linear operator $g \colon Y \to \mathbb{C}$ (which is an element of $Y^\ast$) to the bounded linear operator $g \circ T \colon X \to \mathbb{C}$ (an element of $X^\ast$).If $T$ is a bounded linear operator, then so is $T^\ast$.

- For a metric space $X$, we say a subset $M \subseteq X$ is compact if every open cover of $M$ has a finite subcover — in other words, for any collection $\mathcal{U}$ of open sets whose union contains $M$, we can find a finite subcollection of $\mathcal{U}$ whose union still contains $M$.For a metric space $X$, we say a subset $M \subseteq X$ is sequentially compact if every sequence $(x_n) \subseteq M$ has a subsequence converging to some point in $M$.Compactness and sequential compactness are equivalent (for metric spaces).The reason there's two separate terms is because both can be defined in greater generality for general topological spaces, and there they're not necessarily equivalent. In this post, we'll make use of both notions.

The main focus of this post is a result about compact operators, so now we’ll discuss what it means for an operator to be compact. (We’ll only consider the case where we’re working with bounded linear operators between two Banach spaces.)

There’s an equivalent characterization of when an operator is compact, which may make it more clear where the name comes from. (In the post, we’re going to make use of both characterizations.)

We’ll use $\operatorname{Cl}(M)$ to refer to the closure of a subset $M$, so the condition here states that $\operatorname{Cl}(TM) \subseteq Y$ is compact (as a metric space) whenever $M \subseteq X$ is bounded. We’ll refer to this condition as $(\star)$.

Now we'll prove the forwards direction — we'll suppose that $T$ is compact (as in the original definition) and show that it satisfies $(\star)$. Fix some bounded set $M \subseteq X$. We want to show $\operatorname{Cl}(M)$ is compact, and we'll do so by showing that it's sequentially compact — i.e., that any $(y_n) \subseteq \operatorname{Cl}(TM)$ has a convergent subsequence whose limit is also in $\operatorname{Cl}(TM)$.

First, to apply the compactness of $T$, we really want to be working with a sequence in $TM$ rather than its closure, so the first step is to replace $(y_n) \subseteq \operatorname{Cl}(TM)$ with a sequence $(y_n') \subseteq TM$ that's 'close' to it — since $TM$ is dense in its closure, for each $n \in \mathbb{N}$ we can find some $y_n' \in TM$ with $\lVert y_n - y_n'\rVert < \frac{1}{n}$, and since $y_n' \in TM$, we can find $x_n \in M$ with $y_n' = Tx_n$.

And now the sequence $(x_n)$ is bounded (as it's contained in $M$, which is bounded), so by the compactness of $T$, its image $(y_n') = (Tx_n) \subseteq Y$ must have a convergent subsequence. And since $\lVert y_n - y_n'\rVert \to 0$ (as $n \to \infty$), this means the corresponding subsequence of $(y_n)$ is convergent as well.

Finally, we've found a subsequence of $(y_n)$ that converges to some point $y \in Y$. But since $\operatorname{Cl}(TM)$ is closed and each $y_n$ is in $\operatorname{Cl}(TM)$, this means $y \in \operatorname{Cl}(TM)$ as well. This proves that $\operatorname{Cl}(TM)$ is sequentially compact (and therefore compact), so we're done.

The proof

We’ll now prove the main theorem. Suppose that $T \colon X \to Y$ is compact. Our goal is to show that $T^\ast \colon Y^\ast \to X^\ast$ is compact as well; using the definition of a compact operator, this means we’ve got some bounded sequence $(g_n) \subseteq Y^\ast$, and we want to show that $(T^\ast g_n) \subseteq X^\ast$ has a convergent subsequence.

Step 1 — reformulating the conclusion

First, we’re going to find a sufficient condition for a sequence $(T^\ast g_n) \subseteq X^\ast$ to be convergent that’s more convenient to work with (and we’re going to find a subsequence satisfying this property instead).

Note that $K$ is compact (because $T$ is compact, and $B \subseteq X$ is bounded) — this is the one place where we’re going to use the compactness of $T$. (After this, $T$ will basically disappear from the picture.)

Step 2 — finding a sequence of representatives

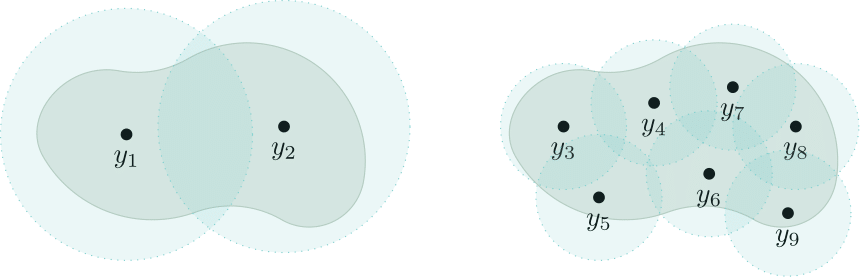

Now our goal is to find a subsequence $(g_n’) \subseteq (g_n)$ satisfying the condition of Claim 4. The first step towards doing so is finding a countable sequence of ‘representatives’ $y_1$, $y_2$, $\ldots$ for $K$ with certain nice properties. The reason for this is that we’re then going to construct our subsequence $(g_n’) \subseteq (g_n)$ such that it converges pointwise at each of these representatives $y_i$, and argue that this implies the desired conclusion.

Then we can take $(y_i)$ to consist of the points in $S_1$, then $S_2$, then $S_3$, and so on (in that order).

This will have the desired property — given any $\varepsilon > 0$, we can fix $n \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $\frac{1}{n} \leq \varepsilon$. Then every $y \in K$ is within $\varepsilon$ of some point in $S_n$, so we can take $N = \lvert S_1\rvert + \cdots + \lvert S_n\rvert$.

Step 3 — defining the subsequence

Now we’re going to define our subsequence $(g_n’) \subseteq (g_n)$, so that it has the following property.

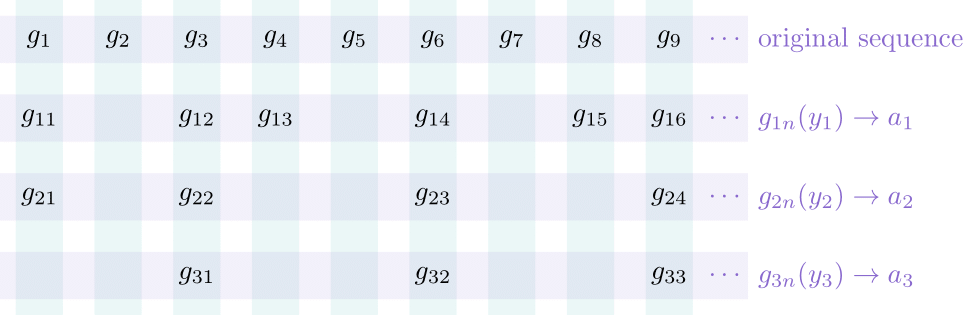

First, we know the sequence $(g_n)$ is bounded (by assumption), so there's some $c$ such that $\lVert g_n\rVert \leq c$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$. This means $\lvert g_n(y_1)\rvert \leq c\lVert y_1\rVert$ for all $n$, so the sequence $(g_n(y_1))$ is a bounded sequence in $\mathbb{C}$, which means it has a convergent subsequence (as it's a sequence in a compact subset of $\mathbb{C}$). So we can define a subsequence $(g_{n1}) \subseteq (g_n)$ such that $(g_{n1}(y_1))$ is convergent.

Next, we're going to further restrict this subsequence to deal with $y_2$ — we have $\lvert g_{n1}(y_2)\rvert \leq c\lVert y_2\rVert$ for all $n$, so the sequence $(g_{n1}(y_2))$ is also a bounded sequence in $\mathbb{C}$, which means it also has a convergent subsequence. So we can define a subsequence $(g_{n2}) \subseteq (g_{n1})$ such that $(g_{n2}(y_2))$ is convergent.

And we can continue doing this to get a nested list of subsequences $(g_n) \supseteq (g_{n1}) \supseteq (g_{n2}) \supseteq \cdots$ such that for each fixed $i \in \mathbb{N}$, the sequence $(g_{ni}(y_i)) \subseteq \mathbb{C}$ is convergent.

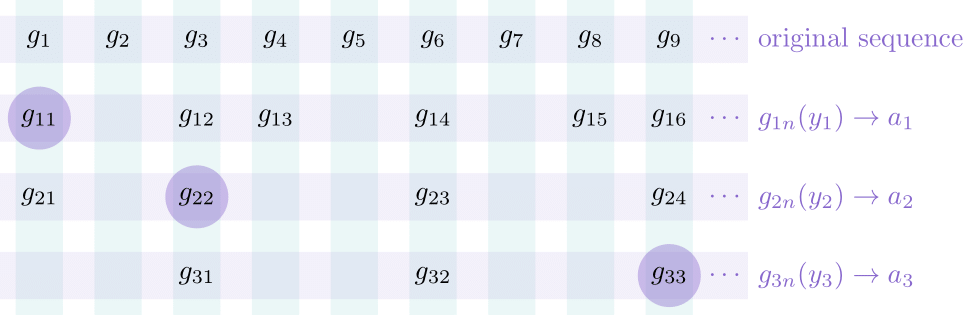

Finally, we define the subsequence $(g_n')$ by $g_n' = g_{nn}$ for each $n \in \mathbb{N}$ — so we're essentially taking the 'diagonal' of our list of nested subsequences.

(For example, in the above picture our sequence $(g_n')$ begins with $g_1$, $g_3$, $g_9$, $\ldots$.)

To see that this works, fix some $i \in \mathbb{N}$. Then if we take the sequence $(g_n'(y_i))$ and remove the first $i - 1$ terms, the resulting sequence is a subsequence of $(g_{ni}(y_i))$, which is convergent by construction; so this means $(g_n'(y_i))$ is convergent as well.

Step 4 — concluding

Finally, we’re ready to conclude — we’ll use the fact that $(y_i)$ forms a nice sequence of representatives for $K$ (from Claim 5) together with the fact that $(g_n’)$ converges pointwise at each $y_i$ (from Lemma 6) to conclude that $(g_n’)$ satisfies the condition described in Claim 4.

Now fix $\varepsilon > 0$. Then using Claim 5, we can first find a constant $M$ such that for every $y \in K$, there is some $i \in \{1, \ldots, M\}$ with $\lVert y - y_i\rVert \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{4c}$; fix this value of $M$.

Then for each $i \in \{1, \ldots, M\}$, we know the sequence $(g_n'(y_i))$ is convergent and therefore Cauchy (by Lemma 6), so there is some $N_i$ such that for all $m, n \geq N_i$ we have $\lVert g_m'(y_i) - g_n'(y_i)\rVert \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2}$.

Finally, let $N = \max\{N_1, \ldots, N_M\}$. To see that this has the desired property, consider any $y \in K$, and fix $y_i$ with $i \in \{1, \ldots, M\}$ such that $\lVert y - y_i\rVert \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{4c}$. Then we can write \[\lVert g_m'(y) - g_n'(y)\rVert \leq \lVert g_m'(y) - g_m'(y_i)\rVert + \lVert g_m'(y_i) - g_n'(y_i)\rVert + \lVert g_n'(y_i) - g_n'(y)\rVert\] by the triangle inequality. (The intuition here is that we know $g_m'$ and $g_n'$ should be 'close' at $y_i$, and we know $y$ should be close to $y_i$, so we should be able to bound each of these terms.)

For the first term, we have \[\lVert g_m'(y) - g_m'(y_i)\rVert \leq \lVert g_m'\rVert \lVert y - y_i\rVert \leq c\cdot \frac{\varepsilon}{4c} = \frac{\varepsilon}{4}\] (the first inequality is by the definition of the operator norm of $g_m'$). We can do the same for the last term to get that it's at most $\frac{\varepsilon}{4}$ as well. Finally, for the middle term, we have \[\lVert g_m'(y_i) - g_n'(y_i)\rVert \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2},\] since we know $m, n \geq N \geq N_i$ and we defined $N_i$ to guarantee this inequality holds.

Putting these together gives that \[\lVert g_m'(y) - g_n'(y)\rVert \leq \frac{\varepsilon}{4} + \frac{\varepsilon}{2} + \frac{\varepsilon}{4} = \varepsilon\] for all $m, n \geq N$ and $y \in K$, as desired.

This concludes the proof of Theorem 1 — we’ve started with an arbitrary bounded sequence $(g_n) \subseteq Y^*$ and obtained a subsequence $(g_n’) \subseteq (g_n)$ satisfying the condition of Claim 4 (using Claim 5 to choose a nice set of representatives, Lemma 6 to find a subsequence converging pointwise at each representative, and finally using the triangle inequality to get the conclusion, as stated in Claim 7), which by Claim 4 means that the sequence $(T^\ast g_n’)$ is convergent.