Tournament of Towns

This winter, I looked at several problems from the Tournament of Towns; here are some that I especially liked. (The last two are among my favorite problems of all time.)

Let $[n]!$ denote the product $1 \times 11 \times 111 \times \cdots \times (11\cdots 1)$ (where the last term has $n$ digits). Prove that $[n + m]!$ is divisible by $[n]!\times[m]!$.

We have $[n]! = \frac{10 - 1}{9} \cdot \frac{10^2 - 1}{9} \cdots \frac{10^n - 1}{9}$, so it suffices to show \[\prod_{i = 1}^n (10^i - 1) \cdot \prod_{i = 1}^m (10^i - 1) \mid \prod_{i = 1}^{m + n} (10^i - 1).\] We'll show that for all primes $p$, the $\nu_p$ of the RHS is at least $\nu_p$ of the LHS.

Suppose $p$ is relatively prime to $10$ (otherwise $p$ cannot divide either side), and let $d = \operatorname{ord}_p 10$. Then only the terms with $i \mid d$ are relevant. If $ad$ and $bd$ are the greatest multiples of $d$ at most $n$ and $m$, respectively, then $(a + b)d \leq n + m$, so it suffices to show \[\sum_{i = 1}^a \nu_p(10^{id} - 1) + \sum_{i = 1}^b \nu_p(10^{id} - 1) \leq \sum_{i = 1}^{a + b} \nu_p(10^{id} - 1).\] But we have \[\nu_p(10^{id} - 1) = \nu_p(10^d - 1) + \nu_p(id) = \nu_p(10^d - 1) + \nu_p(i)\] by LTE. So it suffices to show \[\sum_{i = 1}^a \nu_p(i) + \sum_{i = 1}^b \nu_p(i) \leq \sum_{i = 1}^{a + b} \nu_p(i),\] which is true as $\binom{a + b}{a}$ is an integer.

Suppose $p$ is relatively prime to $10$ (otherwise $p$ cannot divide either side), and let $d = \operatorname{ord}_p 10$. Then only the terms with $i \mid d$ are relevant. If $ad$ and $bd$ are the greatest multiples of $d$ at most $n$ and $m$, respectively, then $(a + b)d \leq n + m$, so it suffices to show \[\sum_{i = 1}^a \nu_p(10^{id} - 1) + \sum_{i = 1}^b \nu_p(10^{id} - 1) \leq \sum_{i = 1}^{a + b} \nu_p(10^{id} - 1).\] But we have \[\nu_p(10^{id} - 1) = \nu_p(10^d - 1) + \nu_p(id) = \nu_p(10^d - 1) + \nu_p(i)\] by LTE. So it suffices to show \[\sum_{i = 1}^a \nu_p(i) + \sum_{i = 1}^b \nu_p(i) \leq \sum_{i = 1}^{a + b} \nu_p(i),\] which is true as $\binom{a + b}{a}$ is an integer.

Prove that for $n \geq 2$, the integer \[1^1 + 3^3 + 5^5 + \cdots + (2^n - 1)^{2^n - 1}\] is a multiple of $2^n$ but not a multiple of $2^{n + 1}$.

Induct on $n$. In the base case $n = 2$, $1^1 + 3^3 = 28$ is a multiple of $4$ but not $8$.

Now suppose $n \geq 3$ and assume this is true for $n - 1$, so \[1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^{n - 1} - 1)^{2^{n - 1} - 1} \equiv 2^{n - 1} \pmod{2^n}.\] Now note that for all odd $x$, we have \[\nu_2(x^{2^{n - 1}} - 1) = \nu_2(x^2 - 1) + \nu_2(2^{n - 2}) \geq n + 1,\] so then $x^{2^{n - 1}}$ is always $1$ mod $2^{n + 1}$. So then \[(x + 2^{n - 1})^{x + 2^{n - 1}} \equiv (x + 2^{n - 1})^x \equiv x^x + x^x \cdot 2^{n - 1},\] since $2(n - 1) \geq n + 1$. So this means \[1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^n - 1)^{2^n - 1} \equiv (2 + 2^{n - 1})(1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^{n - 1} - 1)^{2^{n - 1} - 1}) \pmod{2^{n + 1}}.\] But $2 + 2^{n - 1}$ is even, and the second sum is $2^{n - 1}$ mod $2^n$ by the induction hypothesis, so then the original sum is $2^n$ mod $2^{n + 1}$, as desired.

Now suppose $n \geq 3$ and assume this is true for $n - 1$, so \[1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^{n - 1} - 1)^{2^{n - 1} - 1} \equiv 2^{n - 1} \pmod{2^n}.\] Now note that for all odd $x$, we have \[\nu_2(x^{2^{n - 1}} - 1) = \nu_2(x^2 - 1) + \nu_2(2^{n - 2}) \geq n + 1,\] so then $x^{2^{n - 1}}$ is always $1$ mod $2^{n + 1}$. So then \[(x + 2^{n - 1})^{x + 2^{n - 1}} \equiv (x + 2^{n - 1})^x \equiv x^x + x^x \cdot 2^{n - 1},\] since $2(n - 1) \geq n + 1$. So this means \[1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^n - 1)^{2^n - 1} \equiv (2 + 2^{n - 1})(1^1 + 3^3 + \cdots + (2^{n - 1} - 1)^{2^{n - 1} - 1}) \pmod{2^{n + 1}}.\] But $2 + 2^{n - 1}$ is even, and the second sum is $2^{n - 1}$ mod $2^n$ by the induction hypothesis, so then the original sum is $2^n$ mod $2^{n + 1}$, as desired.

It makes sense to induct because the sum is pretty intractable on its own, but when you lift from $2^n$ to $2^{n + 1}$, a lot of the terms are either the same or closely related.

Some of the integers $1$, $2$, $\ldots$, $n$ have been colored red so that for each triplet of red numbers $a$, $b$, $c$ (not necessarily distinct), if $a(b - c)$ is a multiple of $n$ then $b = c$. Prove that there are no more than $\varphi(n)$ red numbers.

Let $p_1 < p_2 < \cdots < p_r$ be the primes dividing $n$ which divide some red number, and $q_1$, $q_2$, $\ldots$, $q_s$ the primes dividing $n$ which don't divide any red number. If $r = 0$ then all red numbers are relatively prime to $n$ so there are at most $\varphi(n)$ red numbers; now assume $r \geq 1$.

There are at most $\frac{n}{p_r} \cdot \prod \frac{q_i - 1}{q_i}$ red numbers.

Let $n = p_r\cdot m$, so $m$ is divisible by each of the $q_i$. Then each residue class mod $m$ contains at most one red number (if $b \equiv c \pmod{m}$, then take $a$ to be a red multiple of $p_r$, so $a(b - c)$ is a multiple of $n$). Additionally, all red numbers are relatively prime to each $q_i$, so all red residues mod $m$ are relatively prime to each $q_i$ as well. So then there are at most $m \prod \frac{q_i - 1}{q_i}$ red numbers.

But we have \[\varphi(n) = n \cdot \prod_{i = 1}^r \frac{p_i - 1}{p_i} \cdot \prod_{i = 1}^s \frac{q_i - 1}{q_i}.\] We have the bound \[\prod_{i = 1}^r \frac{p_i - 1}{p_i} \geq \prod_{i = 2}^{p_i} \frac{i - 1}{i} = \frac{1}{p_i},\] so then our bound on the count of red numbers is at most $\varphi(n)$. You can start by trying small cases — here the small case is when we only have one prime dividing $n$ with a red multiple, since having none gives exactly $\varphi(n)$. If we look at which residues are allowed then we get exactly $\frac{n}{p}\prod \frac{q - 1}{q}$. Then if we try to go to a more general case, we realize that there isn't really a much better bound we can get (at least, not one that I could find), so we probably still have to use this bound — and then thinking about size a bit finishes.

Initially, the number $6$ is written on a blackboard. On the $n$th step (for $n \geq 1$), if the number $k$ is on the blackboard, it is replaced with $k + \gcd(k, n)$. Prove that at each step, the number on the blackboard increases either by $1$ or by a prime number.

The first step is $6 \to 7$, the second step is $7 \to 8$, and the third step is $8 \to 9$.

Suppose that after step $n$, the number on the blackboard is $3n$. Then if the number next increases by more than $1$ on step $m$, it increases by a prime and becomes $3m$.

We have that $m$ is the smallest integer greater than $n$ for which \[\gcd(m, 3n + m - n - 1) = \gcd(m, 2n - 1) > 1.\] But if $p$ is any prime dividing $2n - 1$, then $n \equiv \frac{p + 1}{2} \pmod{p}$, so the smallest $m > n$ with $p \mid m$ is \[m = n + \frac{p - 1}{2}.\] So then the first $m$ for which the gcd is not $1$ is $m = n + \frac{p - 1}{2}$ where $p$ is the smallest prime dividing $2n - 1$, and here the gcd is \[\gcd(2n + p - 1, 2n - 1) = p.\] So step $m$ is \[3n + \frac{p - 1}{2} - 1 \to 3n + \frac{p - 1}{2} - 1 + p = 3m,\] as desired.

Since after step $3$ the number is $3\cdot 3$, by induction this means all additions are $1$ or prime, and each prime addition results in $3m$ on the board after turn $m$. I think this is a pretty rigid problem — the idea is to try out the process for small values of $n$, and then you notice that there's a pattern: every nontrivial jump ends up in a position $(n, 3n)$, which is surprising but turns out to be not that hard to prove. Maybe it is even expected that the sequence should have some nice property like this, because if there's no good relationship between $n$ and $k$, the problem seems pretty intractable. But even without that heuristic, doing small cases is a good idea.

In every cell of a square table is a number. The sum of the largest two numbers in each row is $a$ and the sum of the largest two numbers in each column is $b$. Prove that $a = b$.

Assume not, so WLOG $a < b$. Label the rows and columns $1$ through $n$. Draw a graph on $n$ vertices and for each column, draw an edge between the row numbers with the two greatest elements of that column (breaking ties arbitrarily) — multiple edges between two vertices are allowed.

This graph has $n$ vertices and $n$ edges, so it must contain a cycle $(r_1r_2\cdots r_k)$, possibly of length $2$. Suppose edge $r_ir_{i + 1}$ corresponds to column $c_i$. Then if $x(r, c)$ denotes the entry in $(r, c)$, we have \[\sum x(r_i, c_i) + x(r_{i + 1}, c_i) = bn\] by looking at columns. But \[\sum x(r_i, c_{i - 1}) + x(r_i, c_i) \leq an\] by looking at rows (since each term is at most the sum of the two largest numbers in each row). But these are the same sum, so $bn \leq an$, contradiction as $a < b$.

This graph has $n$ vertices and $n$ edges, so it must contain a cycle $(r_1r_2\cdots r_k)$, possibly of length $2$. Suppose edge $r_ir_{i + 1}$ corresponds to column $c_i$. Then if $x(r, c)$ denotes the entry in $(r, c)$, we have \[\sum x(r_i, c_i) + x(r_{i + 1}, c_i) = bn\] by looking at columns. But \[\sum x(r_i, c_{i - 1}) + x(r_i, c_i) \leq an\] by looking at rows (since each term is at most the sum of the two largest numbers in each row). But these are the same sum, so $bn \leq an$, contradiction as $a < b$.

I think this is an arrows problem — the idea is that you draw a vertical line for each column connecting the two largest numbers in that column, and then you can get a cycle by adding in horizontal lines, which are at most the largest numbers in the rows.

There are $64$ towns in a country, and some pairs of towns are connected by roads but we don't know these pairs. We may choose any pair of towns and find out whether they are connected by a road. Our aim is to determine whether it is possible to travel between any two towns using roads. Prove that there is no algorithm which would enable us to do this in less than $2016$ questions.

Call the person answering us the oracle; we'll show that the oracle can ensure that at every step until the end, the current knowledge is compatible with both the graph being connected and not.

Color an edge red if the oracle answers no, and blue if yes. Define a blob to be a set of vertices $S$ such that all edges in $S$ are drawn, and the blue edges form exactly a tree. Call a position great if it is a collection of blobs (possibly with size 1) so that there are no blue edges between distinct blobs.

Then the oracle can preserve greatness: suppose the position is great, and we query $uv$ with $u$ in blob $S$ and $v$ in blob $T$. The oracle answers no unless every other edge between blobs $S$ and $T$ has been queried (and colored red), in which case he answers yes.

This preserves greatness, as an answer of yes merges the blobs into a bigger blob. The graph will end up connected, but in the last turn there were two blobs, and if the oracle had answered no instead then the graph would be disconnected. So this works.

Color an edge red if the oracle answers no, and blue if yes. Define a blob to be a set of vertices $S$ such that all edges in $S$ are drawn, and the blue edges form exactly a tree. Call a position great if it is a collection of blobs (possibly with size 1) so that there are no blue edges between distinct blobs.

Then the oracle can preserve greatness: suppose the position is great, and we query $uv$ with $u$ in blob $S$ and $v$ in blob $T$. The oracle answers no unless every other edge between blobs $S$ and $T$ has been queried (and colored red), in which case he answers yes.

This preserves greatness, as an answer of yes merges the blobs into a bigger blob. The graph will end up connected, but in the last turn there were two blobs, and if the oracle had answered no instead then the graph would be disconnected. So this works.

This is essentially the strategy of saying yes unless forced to say no — if you have a connected blue subgraph and the other edges between vertices in that subgraph have not been colored red, then you don't ever have to query those edges. Any strategy that preserves greatness and ends with the graph connected should work; in particular saying no unless that would disconnect the graph works as well.

Let $p$ and $q$ be two coprime positive integers. A frog hops along the number line such that on each hop, it moves either $p$ units to the right or $q$ units to the left. Eventually, the frog returns to the initial point. Prove that for every positive integer $d < p + q$, there are two numbers visited by the frog which differ by $d$.

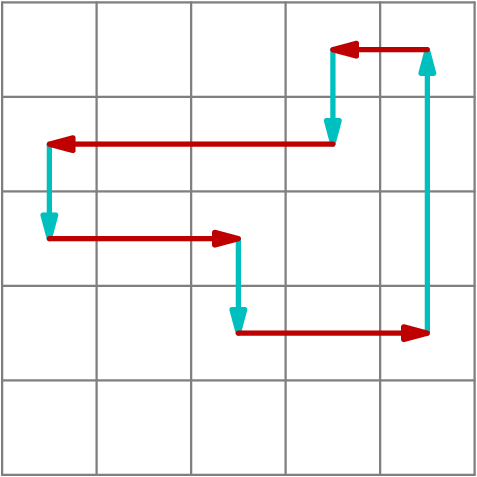

Write the list of jumps $+p$ and $-q$ made by the frog in a circle, so there are $kq$ points on the circle labelled $+p$ and $kp$ points labelled $-q$, in some order. Then it suffices to show that there is some subset of consecutive points on this circle whose sum of labels is exactly $d$.

By Bezout's Theorem there are positive integers $a$ and $b$ with $d = ap - bq$. Look at subsets of exactly $a + b$ consecutive points on the circle. Then it suffices to show there is a subset with at most $a$ points labelled $+p$, and a subset with at least $a$ points labelled $+p$ — as we walk around the circle (taking the subset starting at each point), the number of points $+p$ in the subset changes by $0$ or $\pm 1$ each step, so by Discrete IVT there then must exist a subset with exactly $a$ points $+p$.

First assume for contradiction that all subsets have at least $a + 1$ points labelled $+p$. Then sum over all $k(p + q)$ subsets. Each point is counted in $a + b$ subsets, and there are exactly $kq$ points $+p$, so then \[k(p + q)(a + 1) \leq kq(a + b).\] This implies $ap - bq \leq -p - q$, contradiction. Similarly, if all subsets have at most $a - 1$ points $+p$, then \[k(p + q)(a - 1) \geq kq(a + b),\] which implies $ap - bq \geq p + q$, contradiction.

So then there exists a subset with at most $a$ points $+p$, and a subset with at least $a$ points $+p$, so by Discrete IVT there exists one with exactly $a$ points $+p$, and this subset sums to exactly $d$.

By Bezout's Theorem there are positive integers $a$ and $b$ with $d = ap - bq$. Look at subsets of exactly $a + b$ consecutive points on the circle. Then it suffices to show there is a subset with at most $a$ points labelled $+p$, and a subset with at least $a$ points labelled $+p$ — as we walk around the circle (taking the subset starting at each point), the number of points $+p$ in the subset changes by $0$ or $\pm 1$ each step, so by Discrete IVT there then must exist a subset with exactly $a$ points $+p$.

First assume for contradiction that all subsets have at least $a + 1$ points labelled $+p$. Then sum over all $k(p + q)$ subsets. Each point is counted in $a + b$ subsets, and there are exactly $kq$ points $+p$, so then \[k(p + q)(a + 1) \leq kq(a + b).\] This implies $ap - bq \leq -p - q$, contradiction. Similarly, if all subsets have at most $a - 1$ points $+p$, then \[k(p + q)(a - 1) \geq kq(a + b),\] which implies $ap - bq \geq p + q$, contradiction.

So then there exists a subset with at most $a$ points $+p$, and a subset with at least $a$ points $+p$, so by Discrete IVT there exists one with exactly $a$ points $+p$, and this subset sums to exactly $d$.

I really like this problem; I think it's a cool combination of local (look at a frame and shift it) and global (sum over all frames) ideas. I think the main realization is that you want to write the jumps in a circle and look at a fixed set of counts (meaning a specific pair of $a$ and $b$) — you can sort of motivate this by the fact that you want to look at something, and keeping track of multiple possible solutions would be hard as these seem pretty unrelated to each other (and there sometimes is only one).

Consider lattice paths of finite length which start from $(0, 0)$ and move only up and right, which we call skeletons. For each skeleton, we define a worm consisting of all unit cells in the plane sharing at least one point with the skeleton. (For example, for the path from $(0, 0)$ to $(1, 0)$, the corresponding worm has six cells). Prove that for every integer $n > 2$, the number of worms which can be tiled by dominoes in exactly $n$ ways is equal to $\varphi(n)$.

First, we're going to find a way to recurse the number of tilings of a worm.

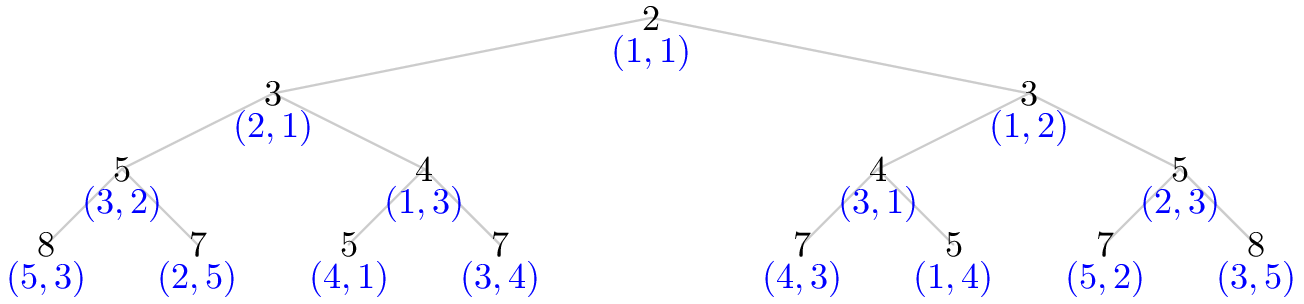

Note that the number of ways to tile the worm of skeleton $(0, 0)$ is $2$, since it is a $2 \times 2$ grid. Also, define the number of ways to tile the worm of the empty skeleton as $1$.

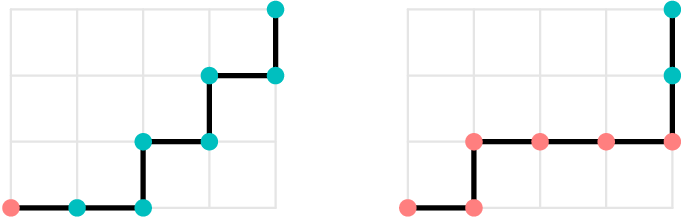

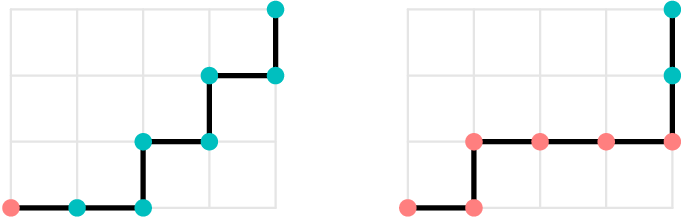

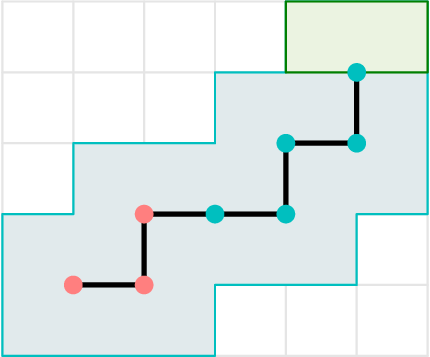

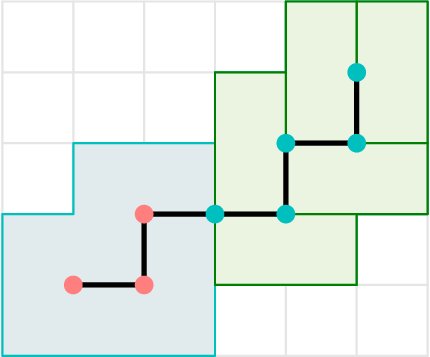

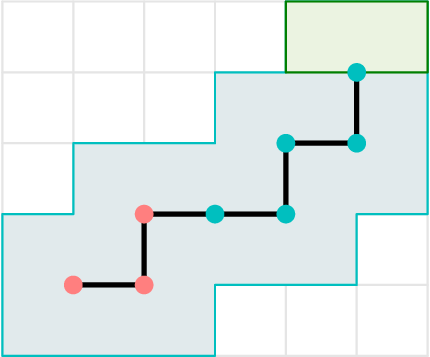

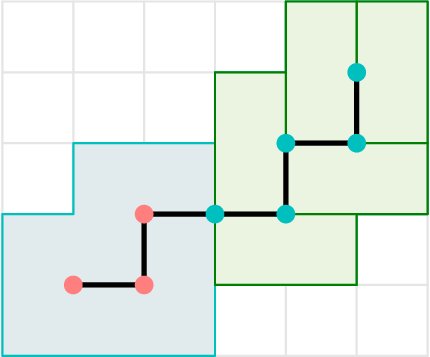

Define the twisty part of a skeleton $S$ to be the maximal sequence of points starting with the end for which the skeleton alternates direction, and define the head of a skeleton to be the remainder not in the twisty part (the head may be empty). Here are some examples, with the heads in red and the twisty parts in blue.

To show this, if $(a, b)$ with skeleton $S$ is a left child, then $a$ is the number of ways for $S$ with its last point removed, and $b$ is the number of ways for the head of $S$.

Then if we go left one step to get skeleton $T$, then $S$ with $a + b$ ways is $T$ with its last point removed, and $S$ with its last point removed is the head of $T$ (since the twisty part is only the last two points), which gives $(a + b, a)$.

Meanwhile, if we go one step right to get skeleton $T$, then $S$ is still $T$ with its last point removed, but the head of $S$ is the head of $T$ (since we went left to get to $S$, and then right to get to $T$, so $T$ swallows the twisty part of $S$), which gives us $(b, a + b)$.

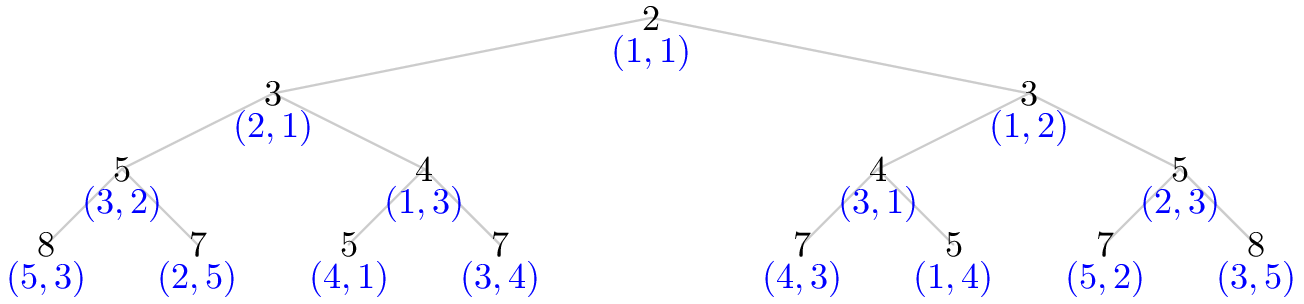

Similar things happen when $S$ is a right child, which proves that our tree is the Euclidean Algorithm tree. But it's clear that every pair $(a, b)$ with $\gcd(a, b) = 1$ occurs exactly once in this tree (since we can trace it back to $(1, 1)$ uniquely), and no pairs with $\gcd(a, b) > 1$ are in this tree. So then the number of occurrences of $n$ in this tree are the number of ways to write $n = a + b$ with $\gcd(a, b) = 1$, which is $\varphi(n)$.

Note that the number of ways to tile the worm of skeleton $(0, 0)$ is $2$, since it is a $2 \times 2$ grid. Also, define the number of ways to tile the worm of the empty skeleton as $1$.

Define the twisty part of a skeleton $S$ to be the maximal sequence of points starting with the end for which the skeleton alternates direction, and define the head of a skeleton to be the remainder not in the twisty part (the head may be empty). Here are some examples, with the heads in red and the twisty parts in blue.

To get the number of ways to tile skeleton $S$, we add the number of ways to tile the skeleton with the last point removed, and the number of ways to tile the head of $S$.

WLOG the last move in the skeleton is vertical. Now if we place a horizontal domino at the top-right corner, the remaining worm is the worm of the skeleton where we delete the last point of $S$.

Now we can make a big tree, where the top entry is the skeleton $(0, 0)$, and when we go down, left means adding a step right while right means adding a step up. At each node, we write the number of ways to tile that skeleton. We also write the two entries we summed according to the previous claim — if this was a left child, then we write the skeleton with the last element removed on the left and the head on the right, while if this was a right child then we do the opposite.

To show this, if $(a, b)$ with skeleton $S$ is a left child, then $a$ is the number of ways for $S$ with its last point removed, and $b$ is the number of ways for the head of $S$.

Then if we go left one step to get skeleton $T$, then $S$ with $a + b$ ways is $T$ with its last point removed, and $S$ with its last point removed is the head of $T$ (since the twisty part is only the last two points), which gives $(a + b, a)$.

Meanwhile, if we go one step right to get skeleton $T$, then $S$ is still $T$ with its last point removed, but the head of $S$ is the head of $T$ (since we went left to get to $S$, and then right to get to $T$, so $T$ swallows the twisty part of $S$), which gives us $(b, a + b)$.

Similar things happen when $S$ is a right child, which proves that our tree is the Euclidean Algorithm tree. But it's clear that every pair $(a, b)$ with $\gcd(a, b) = 1$ occurs exactly once in this tree (since we can trace it back to $(1, 1)$ uniquely), and no pairs with $\gcd(a, b) > 1$ are in this tree. So then the number of occurrences of $n$ in this tree are the number of ways to write $n = a + b$ with $\gcd(a, b) = 1$, which is $\varphi(n)$.

This is one of my favorite problems of all time. It's a rigid problem — the point is to start by trying to figure out how to count the number of tilings of a given worm. You can try placing the tile at the end and drawing the dominoes that are forced, and you notice that you end up with a smaller skeleton with a nice characterization. Once you get the recursion you can try drawing a tree to perform the recursion for small worms, and eventually you notice that this is very similar to the Euclidean Algorithm tree — and you can do the tracking in such a way that it actually becomes the Euclidean Algorithm tree.